Skærtorsdag Homily

By Lars Ottosen of Sankt Jakobs Kirke, Copenhagen, Denmark

For "Maundy Thursday" – April 17, 2025

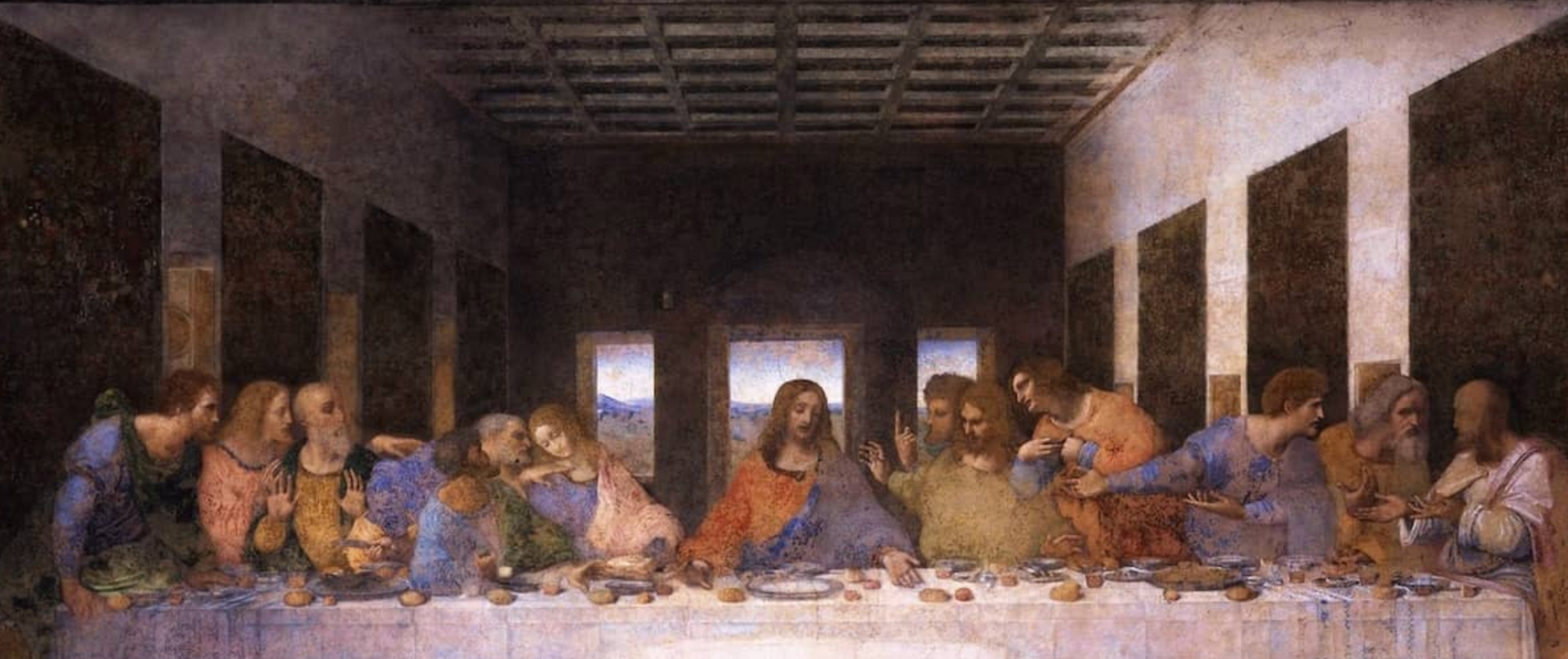

Maundy Thursday. . . The night of Jesus’ final meal. The Last Supper. It’s an image that modernity continues to revisit and preserve. The picture of Jesus sitting at the table with his disciples [as imagined above by Leonardo da Vinci] has been reimagined time and again. New books explore its symbolism, new mysteries surround the making of Leonardo da Vinci’s painting, and Hollywood still makes movies filling cinemas around the world.

It's a scene that continues to fire the imagination of people all over the world. The Son of God, seated at a table He will soon rise from—to be betrayed by a friend, to be abandoned by God and by those closest to Him. And perhaps because of that abandonment, He becomes more the Son of God than ever before.

It’s a reminder: the darkness is real, but the light will rise. Resurrection. Hope. For all of us. Because life, especially life with others, can be hard. Community can divide. It can shut people out, push some down while lifting others up. Society is often a system of difference—a world that measures, categorizes, and highlights every distinction. The philosopher Jean Paul Sartre wrote, “Hell is other people.” Hell is being no one. The one nobody likes. The one betrayed by a neighbor. That’s our primal fear: to be left alone—an infant, or a grown adult—with no one to care for us.

The boxer Willie Pep once said about life in the ring: “First you lose your footwork. Then your reflexes. And finally, your friends.” That’s true of life, too. First we lose our youthful health. Then our strength. And eventually—our friends.

Jesus skipped the first two stages. He died young. But His friends—those He lived long enough to lose. The Last Supper is Jesus saying goodbye. It’s also the moment He centers the meal as the heart of the Spirit’s work in the church that we are part of today.

The greatest gift we can offer one another is ourselves. And that’s what God does every time we gather at the Lord’s table. At a table, you are shaped not only by what you say and hear—but by the food you pass, the space you make, the dignity you offer others. Good table fellowship gives voice and honor to everyone. Hospitality isn’t just the work of the host—it’s the responsibility of everyone at the table. A shared meal is a civilizing act of spirit and community—played out every day, in every society, all over the world.

Because barbarism exists. We see it in Ukraine. We see images of death. We see Ukrainians giving their lives—for their families, their nation, and their freedom.

And before Jesus walks into death Himself, He makes a meal. Not just as an example of how to live with one another—but to establish a new covenant. A new relationship between God and humanity. A relationship where God places Himself at our mercy—surrenders to our freedom.

Disagreement, dialogue, and the right to speak your mind—these are the cornerstones of any free and democratic society. Jesus didn’t come to build a world full of bitter, silent tables where people glare at each other over their food. He came to show us that God is real in our everyday lives.

And along the way, there must be eating and drinking, talking and debating. One of Jesus’ most beautiful human qualities was His joy in sitting down to eat—not just with friends, but with strangers. That joy, that table fellowship, became one of the church’s sacred acts.

Other religions have detailed food laws and rituals surrounding everyday meals. Christianity also gives food a sacred place—but differently. We don't have daily rules around eating. Instead, we take the meal into the very heart of worship.

The Eucharist says: Embrace life with all its beauty. Delight in it. Take it, taste it, and pass it on—to others—as light, and life, and joy.

And in this moment—when war again rages in Europe, when new global tensions are rising, when even American leadership feels uncertain—it is so important to remember: The idea of equal worth for every human being is at the very center of the Christian faith. This is the dignity we are baptized into—the grace we meet again and again at Christ’s table.

Maundy Thursday reminds us to dare to believe that community can be held together by the grace God pours into our cups and gives to us in the bread—through His Son. The one who was betrayed, and who lost Himself—but returned in Spirit and in forgiveness.

And no war, no fear, no uncertainty can shake that faith. The word “Skær” (in Denmark Maundy Thursday is called Skærtorsdag) comes from the old word for “clean.” On this day, Jesus bent to wash Peter’s feet, and Peter didn’t understand. He was confused, maybe even ashamed. But Jesus wanted him to feel clean—not dirty. Because Jesus knew that life can be tough. He knew how society divides. He knew how people are sorted and measured and excluded.

But He also knew—it doesn’t have to be this way. He knew faith can set us free. He knew we don’t have to play out life on a stage where all the roles are locked in place.

A table can offer hope for the future. A sustainable future. A future where we can laugh at ourselves and each other—and not mean harm. A future where we bring our doubts—to God’s table, to one another. Even our doubts about God, and about ourselves, are welcome here.

When Jesus broke the bread and lifted the cup, He knew He was giving Himself to us—as Spirit, as forgiveness, as communion.

A table can gather energies. And we need that now—when the world’s energies are scattered and dangerous. Because food should never divide. It should create identity and togetherness for those gathered—and never hostility toward those who eat differently. A meal should gather the energies of God and humanity—into one shared prism, one that catches the light of the table—and shines it forward in hope.

We’re good at washing our own hands. And when politicians mess up, there’s always a line at the metaphorical sink. But Maundy Thursday isn’t about self-congratulation. It’s a lesson in mercy. First from God. Then, through us.

Are we perfect? No, we are not. Will we get our feet washed every day? Probably not. But we can be something for someone else. We can pass the bread. We can pour the wine. We can pass on freedom.

In the end, maybe it’s the invisible wine—that mysterious joy—that’s the real miracle. That we can all feel the rush of life in our blood, when we open our hearts to the world and to one another. Making wine is, in many ways, like becoming yourself in community. A grape, like a person, only makes sense in relation to others. To be yourself with others is a lifelong, dynamic process. The grape is crushed. Jesus is broken.

And both return—as wine, as joy, as faith, as hope, and as love.

Amen.